DORA: when the financial sector becomes obsessed with data security

Publié le 10/1/2023

By Arnaud Dufournet, Chief Marketing Officer

In our first blog post of 2022 we anticipated that it would be a busy year for the people who draft cybersecurity regulations in Europe. Events proved us to be right. Everything suddenly gathered pace in the last two months of 2022 with the adoption of the new NIS Directive and the DORA Regulation by the European Parliament and then the European Union Council in late November. The new directive and regulation were published in the Official Journal of the European Union on December 27, providing greater visibility over the timetable for their entry into effect.

As you may know, the Digital Operational Resilience Act (DORA) is an EU regulation that is intended to serve as the financial sector’s version of the NIS Directive. The world of finance is certainly no stranger to regulations, but this latest edict proves to be particularly demanding as regards the contractual relationship with IT service providers.

The origins of DORA: operational risk

The 2008 financial crisis shone a spotlight on the connections and mutual dependencies between banks and insurance companies. The Basel II and then Basel III agreements emerged so as to offer protection against operational risk. In 2010, Basel III tightened prudential standards to limit credit risk, but didn’t stop there.

It also introduced the idea that operational risk should be included when evaluating minimum equity requirements. According to the Basel Committee, operational risk is the “risk of loss resulting from inadequate or failed internal processes, people and systems or from external events.”

This very broad definition thus encompasses information system failures, and information systems are taking on an increasingly important role with process digitalization and the use of new technologies (AI, RPA, cloud services, and so on). The 2008 crisis showed that information system failures must definitely be included within operational and systemic risks.

In recent years, the rising threat from cyber attacks has only increased this risk of IT failure. This means failure is no longer caused by technical issues or human error alone; it can also result from malicious intent in the form of cyber attacks, whether criminal in origin or instigated by unfriendly governments seeking economic intelligence.

As cyber threats grow, so does operational risk

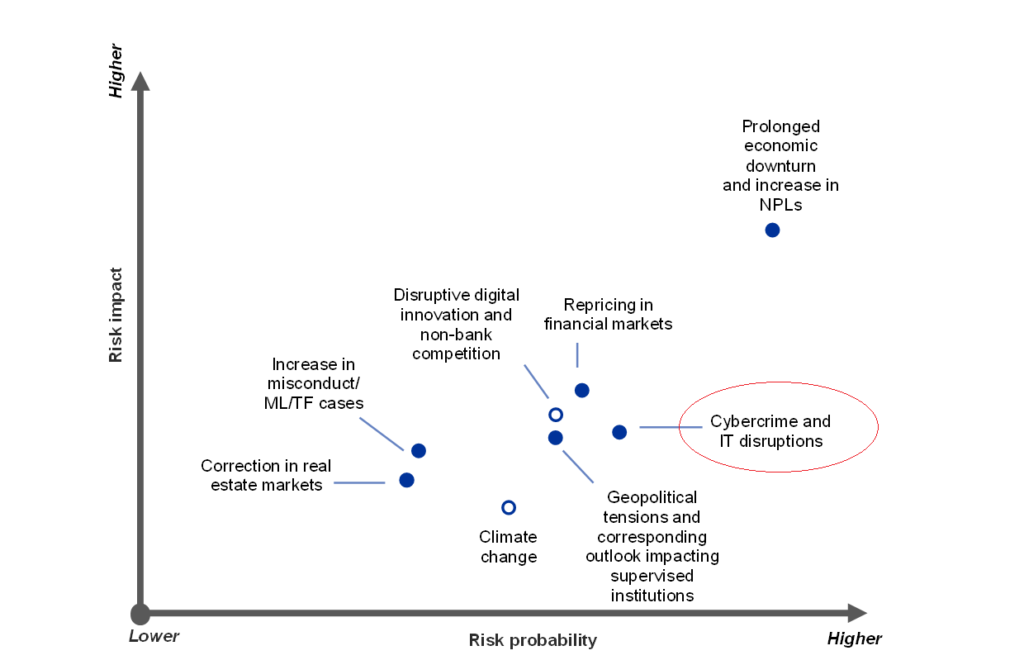

Cyber risk is now identified and monitored by the European Central Bank and other major central banks as well and truly included within the set of systemic risks. We have moreover addressed this issue in a previous blog post [French only] on the banking sector.

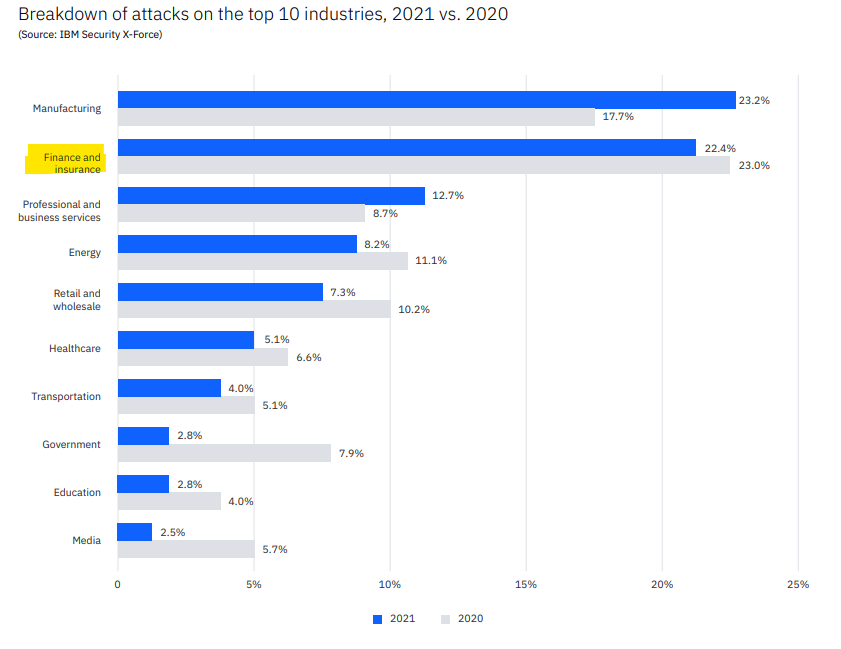

Banking transactions carried over networks and the large amounts of personal data handled are cybercriminals’ main interest. IBM’s X-Force Threat Intelligence Index 2022 reveals once again that the financial sector is undeniably one of the key targets for attacks, just behind manufacturing.

IBM’s findings are that 22% of attacks and incidents reported in 2021 were aimed at the financial sector, primarily banks (70% of these attacks, as against 16% on insurance companies).

The stakes could now scarcely be higher: the possible collapse of the banking system and therefore of our economies. The European Union has grasped the seriousness of the implications, and decided to tackle the issue head-on by developing the concept of digital operational risk.

So after NIS, here’s DORA

In the wake of the NIS Directive, the first version of which was ratified in 2016, the European Commission first started thinking about specific regulation for the financial sector in 2020, with a view to toughening up digital operational resilience. Unlike a directive, which requires transposition into domestic law, a regulation applies as-is in all EU member states.

This regulation has two notable features. The first is its obsession with data security. Availability, authenticity, integrity, and confidentiality are the four criteria that recur time and again throughout the regulation, starting in the definitions of “ICT-related incident” and “operational incident” in Article 3, appearing again in Article 5 on governance and organization, then Article 9 on protection and prevention, and so on.

The second is that this sector-specific regulation concerns not only insurers and credit institutions but also their IT service providers (with the exception of microenterprises). Article 28 of the regulation reiterates the general principle that “financial entities that have in place contractual arrangements for the use of ICT services to run their business operations shall, at all times, remain fully responsible for compliance with, and the discharge of, all obligations under this Regulation and applicable financial services law.” It is therefore impossible to pass the buck onto any external provider.

Paragraph 5 of this same article then says that “When those contractual arrangements concern critical or important functions, financial entities shall, prior to concluding the arrangements, take due consideration of the use, by ICT third-party service providers, of the most up-to-date and highest quality information security standards.” In other words, critical IT service providers are an integral part of risk assessment, and financial institutions must ensure their providers are beyond reproach, security-wise.

The European Union’s thinking starts from the premise, established since attacks such as SolarWinds, that a cyber incident can easily spread to every player in an industry. The aim therefore is to protect the entire supply chain from the risk of attack.

DORA set to boost encryption use

Article 9 of the regulation, on “Protection and prevention,” requires an information security policy to be produced. Paragraph 2 of this article states the measures to be taken to protect data: “Financial entities shall design, procure and implement ICT security policies, procedures, protocols and tools that aim to ensure the resilience, continuity and availability of ICT systems, in particular for those supporting critical or important functions, and to maintain high standards of availability, authenticity, integrity and confidentiality of data, whether at rest, in use or in transit.”

The regulation does not say so, but data encryption meets the authenticity, integrity, and confidentiality obligation here.

This article also recognizes the three intrinsic advantages of a VPN solution that specifically protects these data “in use”, meaning when a user wants to access an information system (IS) to consult them.

Article 30 requires that these same measures to protect data are taken by “ICT third-party service providers.” Such provisions are to be explicitly included in contracts between parties to ensure “availability, authenticity, integrity and confidentiality in relation to the protection of data, including personal data.”

Protecting communications with a trusted VPN

As it is in cybersecurity, trust is a cornerstone of the financial system. This might make DORA’s obsession with availability, authenticity, integrity, and confidentiality easier to understand. Given the connections between networks, an internal or external incident that undermines any one of these four principles could compromise the financial system.

The security visas issued by the French National Cybersecurity Agency (ANSSI) held by TheGreenBow’s VPN clients attest to the high level of security they offer. There are many uses for VPNs in banking, such as protecting remote communications for staff working from home, keeping banking administration traffic secure with an IPsec VPN tunnel, controlling the IS access granted to external contractors using specific configurations in the VPN client, and more besides.

And to face up to the quantum threat, TheGreenBow is already working with major central banks on plans to roll out VPN clients incorporating encryption algorithms that are resistant to quantum attacks. Due to apply from January 17, 2025, stakeholders in the financial sector and their IT service providers have two years left to comply with the DORA Regulation. And given the demands it makes, even two years cannot be viewed as excessive.